The Shadows of Giants

Why Tolkien and Lewis Have Yet to be Matched, and Why Imitation is Not Enough.

I posted a note recently about this topic, which gained a surprising amount of attention. I offer some expanded thoughts below, although I am far from happy with its finished form. I suspect it is an idea I will return to again.

I grew up reading a lot of Christian fiction. Some of it was decent, but most of it ranged from mediocre to awful. The binding thread of much of that material was the phrase “in the tradition of Lewis and Tolkien” somehow associated with it, either directly placed on the cover or given to me by a well-meaning adult who said, “If you like Narnia then you’ll love this!” They were usually wrong. Even at a young age I could tell the difference between the quality of Tolkien and Lewis and their would-be-imitators, who churned out moralizing fairy-worlds without an ounce of the charm or majesty of their inspirations.

Always, when we discuss Christian fantasy, it is always these two men: Tolkien and Lewis. Tollers and Jack sit enthroned above all who came before, and all who came after. Someone versed in the Inklings might bring up their contemporaries, Charles Williams and Owen Barfield, but they will rarely have read them. More often their predecessors will be invoked, George Macdonald and G.K. Chesterton, both admirable and too-little read. But after them things seem to fizzle out. It always comes back to the same two men when we set the standard for what Christian fantasy literature ought to be.

Let me be clear: I do not begrudge the lords their crowns, they are rightly earned and well deserved. My question is this: why have we not seated another lord among the thrones? Why has there been no “successor” to Tolkien and Lewis? There has certainly been no shortage of attempts, as the deluge of poorly written Christian propaganda that I learned to loath in my youth taught me. But none have found a foothold, and none have ascended to join the ranks of the all-time classics. Three clues came to mind when I think about this question, and I will endeavor to draw them into an answer.

First: When we read Lewis and Tolkien and discuss them endlessly, we sometimes forget the caliber of persons we are dealing with. We forget, namely, that both men were geniuses of an uncommon order. Both men could read by the time they were four and write soon after. Their parents almost instantly set them learning Latin and Greek, and both were familiar with French and German, Icelandic and Old Norse. Lewis was familiar with at least seven separate languages, and Tolkien could work in at least fourteen. Both men read Homer and Virgil their original scripts and likely read more books in non-English languages than most of us will read in our own mother tongue in our lifetimes.

Both men were accomplished scholars at Oxford (and later Cambridge, in Lewis’s case.) Each wrote hugely impactful pieces of literary criticism in their specialized fields. Tolkien singlehandedly resurrected Beowulf from a piece of forgotten parchment, picked over by historical vultures looking for points of data, elevating it to a classic text that is now required in English Literature courses. Lewis’s “Preface to Paradise Lost” continues to be cited by Milton scholars, and his works on medieval allegory and cosmology remain some of the most insightful works on their respective subjects. Each man wrote mountains of prose perfecting their thinking, philosophical opinions, and creative minds. They engaged with the best and most impactful philosophy, history, theology, poetry, and prose, not in abstract summaries, but by reading the primary sources themselves.

I do not list their accomplishments to discourage us from attempting to emulate them, but rather to remind us that we are not dealing with “good writers” but men of incredible knowledge and skill. What they consumed, how they consumed it, and the way they thought about what they were doing are a far cry from what we do when we sit down to try to write a story “in their style.” This is our first clue.

Second: When we speak of successors, we generally mean “more of the same.” We are trying to capture that illusive something that Lewis and Tolkien have that we cannot get out of our hearts and minds after encountering it in their works. I think we begin the confusion by grouping the two men together in the first place. Yes, they both possess a similar quality, but no one could confuse Narnia for Middle-Earth, or vice versa.

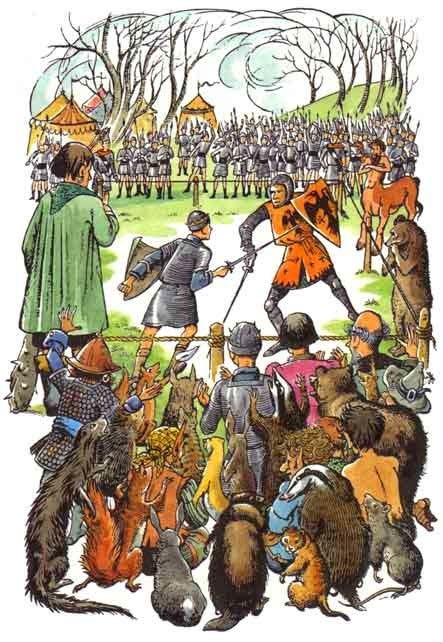

Lewis’s world is a great colorful painting come to life, as though all the nightmares of the pagans, their giants and gods and fauns and centaurs and great beasts, came pouring out in a grand procession, transformed into something almost like a carnival. It is a procession presided over by a talking lion, filled with waddling beavers and dancing nymphs, strange web-footed Marsh-Wiggles and jubilant river gods, and trailed behind by Father Christmas chuckling on his sleigh. And yet in the midst of the carnival there is a profound since of chivalry that seems to come right out of Arthur’s Court. Knights stride among the wheeling masses, vows are taken and given in dignified ceremony. Kings face off in single combat and go to their deaths with smiles on their faces. Father Christmas himself hides weapons of war amid his bags of gifts. The very contrast of the solemnity that lurks among the cavorting figures heightens the whole work. It has all the chaos, order, and color of a medieval tapestry.

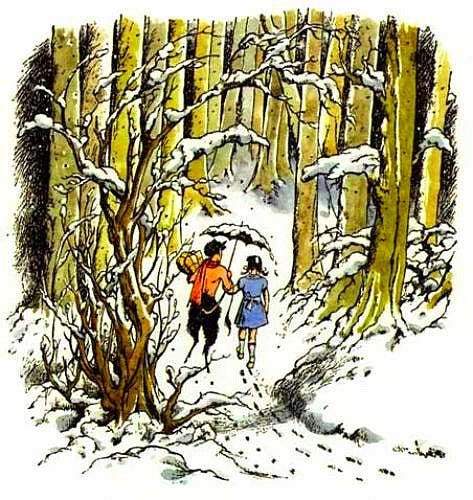

Then we take up Tolkien. We might at first be lulled to think he and Lewis are working in a similar mold by his comic and pastoral scenes of the Shire. But as soon as we step beyond their bounds, we are in a very different world indeed. Here is a world of deep forests and crumbling ruins, of loss and decay. We are in a land of snow-capped peaks and ancient horns that blow across the mournful hills. It is steeped in the spirit of “Northerness” that Tolkien so admired. Here men stride along the wilderness, unthanked and unknown as their grim tasks keep evil at bay. Beauty here is not cavorting (save perhaps for the occasional elf to be glimpsed in the woods) but lies hidden in valleys and caves, sheltered and preserved. Here there is ancient lore, ruined lands, forgotten lineages. Here is a world slowly dying, its glory days faded, their fire kept alive by a handful of souls who remember the times before the present darkness. There is great comedy, of course, and delight to be found. But it is of a very different sort than one finds in Narnia. In Narnia, we feel we have fallen into a medieval tapestry. In Tolkien, we feel we have fallen into an ancient poem, of grand and dark deeds in a forgotten age.

No author has managed to imitate Tolkien; to create the feeling he created in his world and work. At best we have caught glimpses, shadows passing over us that quickly fade. Some have imitated him in the depth and complexity of their worlds, or the scale of their quests, but none have taken us to a place like Middle-Earth or infected us with that joyful sorrow of having been there. Some authors have managed to imitate Lewis, but only in part and never in full. They might capture his fun and delight or play upon his concepts of other worlds and fantastical lands, but none have captured the knightly grandeur that walked hand in hand with the mirth and delight.

The point is that Tolkien and Lewis are not doing the same thing. They are operating in parallel lines, and at times they intersect, but when we mention them in the same breath, we confuse the matter. When mentioned together we are speaking of their impact on literature as a whole, not on the quality of their work as it actually stands. Each author was operating in their own field, making their own way and leaning on their own strengths and passions, and this is our second clue.

Third: We do not live the lives that these men lived. Each man witnessed the massive transformations that came during the course of the twentieth century. They were raised in a world where quiet could still be found, before cell phones and televisions commandeered the airwaves. As young men they fought in the trenches and among the mustard gas of the first world war. They saw the transformation of their society, lived through the air raids and the political crisis of the second world war. Tolkien once remarked that “by 1918, all but one of my close friends were dead.” Lewis recorded, in agonizing detail, the grief of losing his wife Joy after only a few years of marriage. These were men who wrestled with loss and despair. Beyond this, both men were fully committed to the Christian faith in a way I suspect we do not fully appreciate. They did not just talk about their religion or write about it (although Lewis certainly did that) but they lived it, actively, daily, committing themselves to it. The reason that the gospel flows out of every river in Narnia, and undergirds every mountain in middle earth, is because both men took the matter of their souls and the realities of God much more seriously than we tend to understand.

So, what do these clues amount to? We have men of genius who were steeped in great works of literature, men who wrote very distinct stories in clear and separate voices, and men who lived lives of great struggle, turmoil, activity, and faith. My suggestion is this: when we try to write “in the tradition of Lewis and Tolkien,” we make a fatal mistake. We make the mistake of trying to imitate what Tolkien and Lewis wrote rather than getting to grips with what lies behind the writing.

What they wrote is, of course, our chief interest, but it is the result of a lifetime of study, experimentation, thinking, playing, suffering and failed attempts. Neither Lewis or Tolkien wrote primarily to be “authors,” they wrote because their minds were filled with energy and imagination, and the words and worlds came pouring out of them. The material for those words came from their days of reading Homer and Dante and Shakespeare, of the long grueling hours spent memorizing Latin and Greek declensions, their experiences on the battlefield watching men die, and witnessing the long, grinding march of time as they saw the world change around them, and within it all continued to grow in their understanding and love of God. They built up storehouses within their souls and then drew from them when they sat down to write.

If we sit down with a pen or at the keyboard with the hopes of imitating these men, we may make a start, but we will never produce anything close to what they accomplished. At best we will produce cheap copies, shallow and ultimately worthless. To accomplish the real work, we must feed our souls, our minds, and our hearts. We must challenge ourselves, push beyond the goal of merely “writing,” and engage deeply and passionately with things of value. We must read the great works, not because they are old or important, but because within them is beauty and truth and wisdom that will build us up, make us wise, and nourish us. We must try to learn things that stretch our minds, whether that is advanced mathematics or Homeric Greek. We must also not try to sound like Lewis, or like Tolkien because we think “that’s what Christian fantasy sounds like.” We must not write for their time, but for ours, in the voices that ring true and clear within ourselves. We must not write for the spotlight, but because the desire to create wells up within us to the point of bursting. Most importantly, we must put all of these lofty ambitions aside and keep our focus on Christ. We must live lives of prayer, of liturgy, of devotion, of faith being worked out with fear and trembling. Then, if it is our role to do so, what wisdom the Lord has allowed us to gleam will be joined to the power of our imagination and the sharpness of our minds, and it will pour forth into new stories.

We sit in the shade of mighty trees. We cannot simply look up and admire them and wish to become trees ourselves. We must put down roots in rich soil and grow, slowly, painfully, with purpose and faith. We may not, and likely will not, ever know if we attained the lofty branches of our forebears. But the tree is not concerned with how tall it becomes, so long as it continues to reach towards the sun. Let later generations judge if it casts shade worth resting in.

Reading this was like taking a breath after being under water for too long! One of my favourite readings in substack so far.

This is a phenomenal post. I admire how deeply you think on literature. As I was reading, I kept thinking: "What makes up a person?" What we consume and our experiences are a large part of it, and from that soil, we form ourselves into something new. I love how you demonstrated that the Greats were vast consumers of very rich material and that produced very different but both extremely worthy results.

That's what we should be aspiring to. As you say, not imitation of the words or style, but imitation of how to live a life of meaning where suddenly, the words bubble out of you despite yourself.